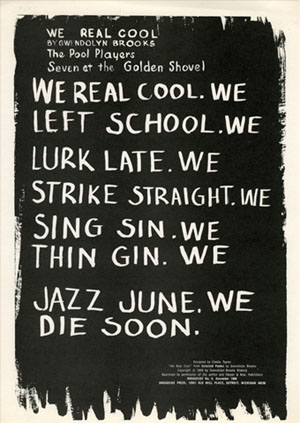

Kyle Schlesinger has a great essay called “A Look at Some Contemporary Poetry Broadsides” in which he discusses the history of poetry broadsides and their contemporary design, over on Evening Will Come. A few excerpts follow, and it’s a fascinating read, with lots of examples.

On the Poetry Broadside in the 20th Century

In twentieth century America, the poetry broadside blossomed in the sixties and seventies. In the revolution of print culture spurred on by the New American Poetry’s intersection with the mimeo revolution and a new wave of innovative printers and book artists, the broadside became something of a radical courier for self-expression as well as a quick, DIY medium for social and political transformation. It served as an ideal way to promote and commemorate events such as Happenings, rock concerts, dance performances, and poetry readings. In turn, the construction and distribution of broadsides, magazines, and pamphlets became popular underground occasions for impromptu gatherings around second-hand Vandercooks, homespun silkscreen equipment, and saddle staplers.

On the Difference Between Broadsides, Handbills, and Pamphlets

It’s an elusive term, but broadsides are usually bigger than handbills and smaller than posters. They are often printed letterpress, but not necessarily. They often contain verse, but that’s not a requirement either. Like pamphlets, some broadsides fold, but that’s just my opinion, others would say that broadsides are a single, unfolded sheet printed on one side only.